- Published on

Teach My Girlfriend GPU 2: Logical Module Division

- Authors

- Name

- Yue Zhang

- Limitations of the Traditional Pipeline

- Enter the Geometry Shader

- Geometry Shader Limitations

- Tessellation: Built for Triangle Subdivision

- The Rise of GPGPU: General-Purpose GPU Computing

- Compute Shaders: Purpose-Built for GPGPU

- Mesh Shaders and Amplification Shaders

- Ray Tracing Pipeline: A New Frontier

This is the second episode of Teach My Girlfriend GPU. Last time, we introduced a basic GPU and what kind of pipeline it should have.As time moved on, new demands arose.So now let’s look at how to evolve from a simple unified pipeline into a more flexible and comprehensive one.

Limitations of the Traditional Pipeline

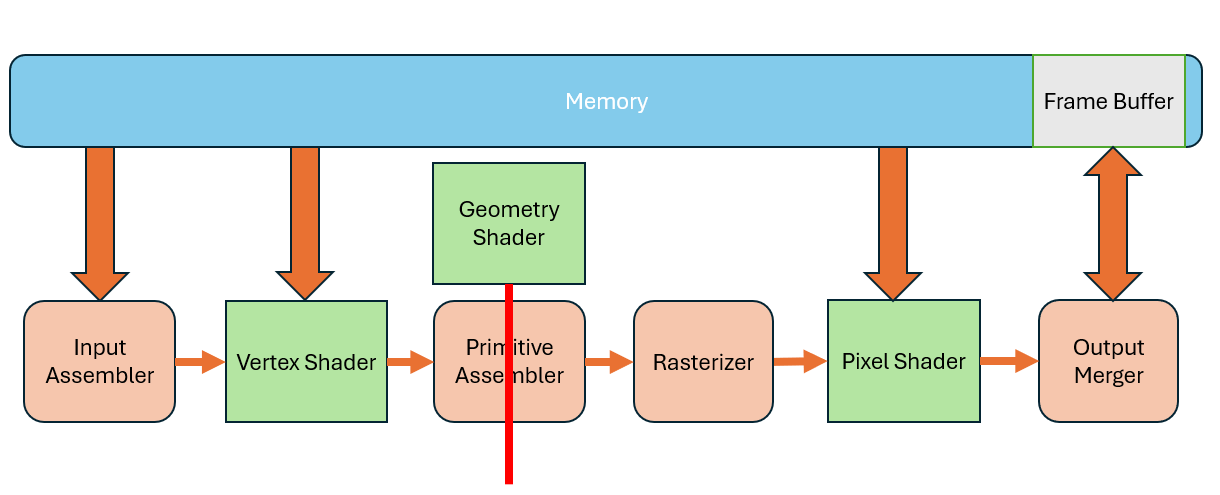

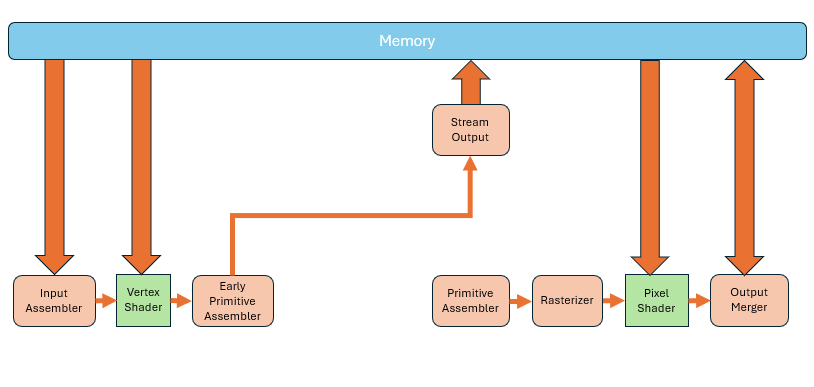

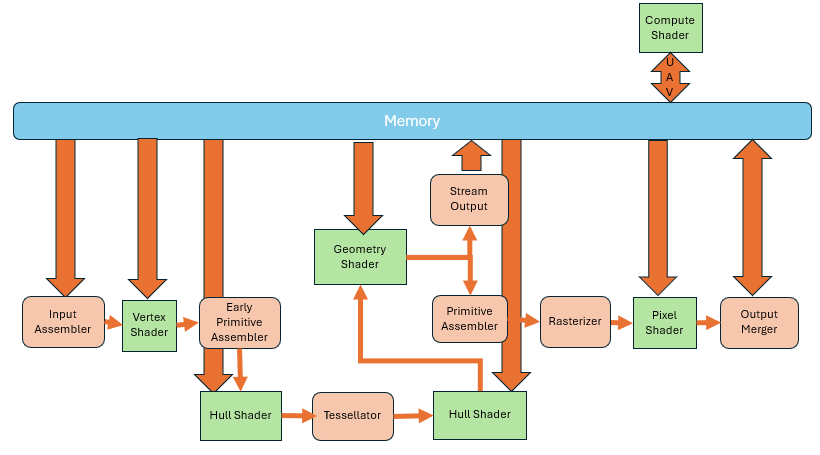

The traditional GPU pipeline—consisting of Vertex Shaders and Pixel Shaders—is built around a single-input, single-output model. Each shader processes one unit of data and produces one result. This works well for vertices and pixels but fails when we need to process a whole primitive like a triangle.

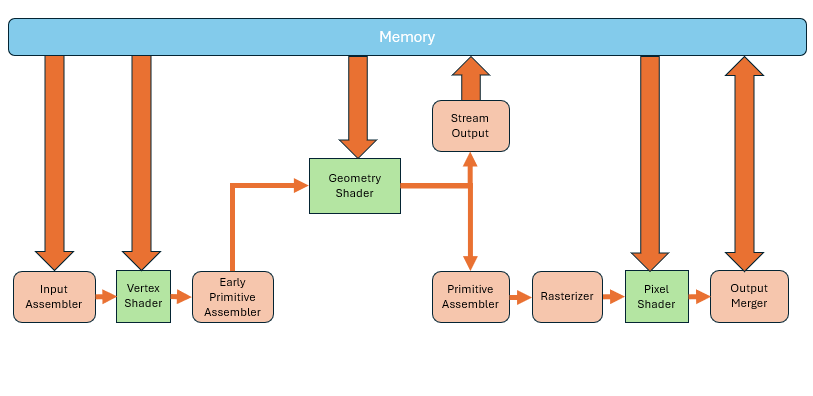

Enter the Geometry Shader

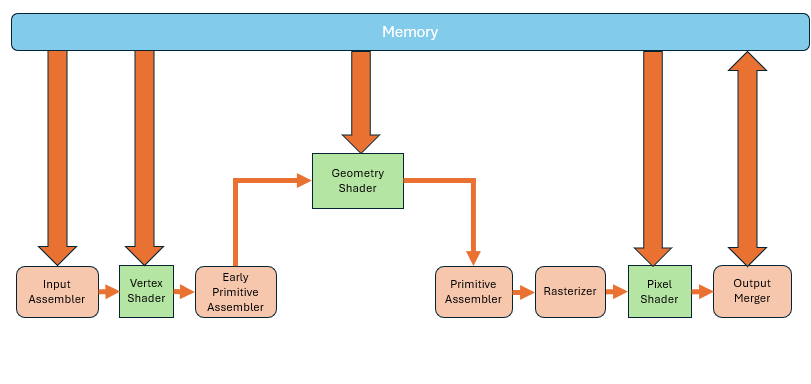

This demand led to a new shader type: the geometry shader. It essentially splits the primitive assembler.

After the vertex shader processes the vertices, the entire primitive is passed into the geometry shader.

NOTE

Early Primitive Assembler's primary role is to prepare these vertex groups for potential processing by the geometry shader, without yet performing the full visibility checks or culling operations. Unlike the main Primitive Assembler, which operates later in the pipeline to finalize the primitives for rasterization—applying clipping, back-face culling, and preparing interpolated data for the rasterize

Then keep going to the rest of the primitive assembler.

Compared to the previous two shader types, it has a big difference that it supports single input, multiple outputs. When one primitive enters, it can output multiple primitives. So, you can move the entire triangle to a new position, or divide one triangle into multiple ones.

Its existence enables the GPU to handle irregular and flexible output tasks. For example, the first triangle may output one, the second five, the third three.

Another difference is that the vertex and pixel shaders are mandatory. If you don’t specify them, the pipeline won’t work at all. But the geometry shader is optional—if omitted, the data just flows to the next stage.

The primitives output by the geometry shader can not only enter primitive assembly and rasterization stages, but can also be written directly to memory. This process is called Stream Output. Of course, you can also skip the geometry shader altogether,and output directly from the vertex shader. This gives us the ability to tap into the middle of the pipeline and extract data. Sometimes we’ll store the results of vertex shader processing and reuse them later to avoid redundant computation.

Of course, you can also skip the geometry shader altogether,and output directly from the vertex shader. This gives us the ability to tap into the middle of the pipeline and extract data. Sometimes we’ll store the results of vertex shader processing and reuse them later to avoid redundant computation.

Geometry Shader Limitations

However, there's a problem here. The geometry shader appears very flexible and can handle many complex tasks. But in practice, the performance gains are minimal. This is because the hardware can't make assumptions for optimization. It has to implement things conservatively. Especially when subdividing a triangle into multiple pieces—it was originally a fixed, well-defined operation. But if you make everything programmable, then the hardware won’t even know whether you’re going to subdivide the triangle. So it becomes impossible to optimize ahead of time.

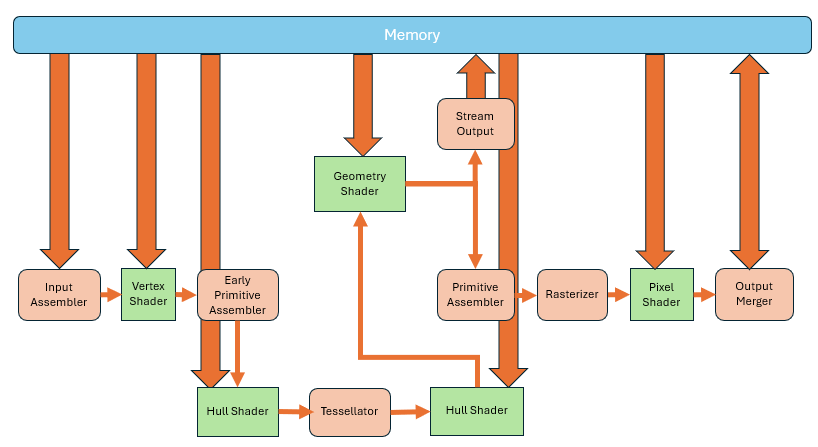

Tessellation: Built for Triangle Subdivision

As the demand for triangle subdivision increased, a dedicated tessellation stage was added after the vertex shader in the GPU pipeline. It’s not a single unit—it consists of three parts.

First, there's a programmable Hull Shader. This allows you to define how each primitive should be subdivided. For example, how many parts the interior should have, or how many segments per edge.

Then there's the fixed-function Tessellator stage, which performs the subdivision using fixed algorithms.

Following that is the Domain Shader, which computes vertex attributes based on the subdivision parameters.

This whole part is also optional. If unused, the data just proceeds directly to the next stage.

The Rise of GPGPU: General-Purpose GPU Computing

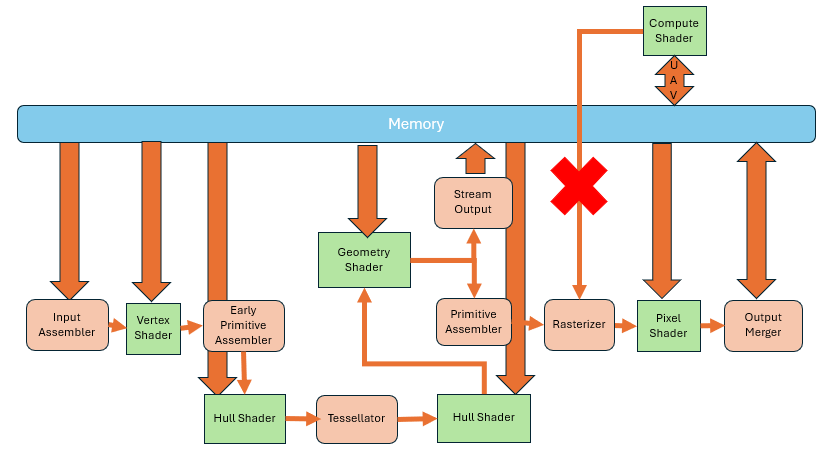

Since GPUs have such powerful compute capabilities, they can be used not only for traditional rendering but also for more general-purpose parallel computation. The earliest method was: rendering a massive triangle that covers the whole screen, and performing general-purpose calculations inside the pixel shader. Each pixel effectively became a thread. This did solve some problems, but the limitation of "single input, single output" remained. Additionally, the data still had to go through unnecessary stages like the rasterizer and the entire graphics pipeline, which was wasteful.

Compute Shaders: Purpose-Built for GPGPU

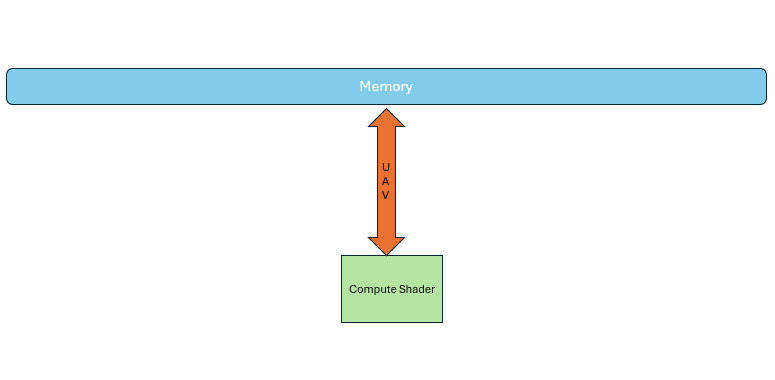

This demand further led to GPUs with hardware support for general-purpose computing. They could now support multiple inputs and outputs, arbitrary reads, and arbitrary writes. No longer was it necessary to pass through those fixed-function pipeline stages. Instead, the compute units on the GPU could be directly used for parallel computation.

This kind of shader is called a Compute Shader.

It exists independently of the graphics pipeline. It operates entirely on memory and imposes fewer restrictions compared to the graphics pipeline. The entire compute pipeline is essentially a single step, making it much closer to conventional software development.

At this point, the GPU pipeline had become very close to what we see today, capable of fulfilling both real-time rendering and general computation needs. At the same time, the GPU pipeline also became very complex.

Could it get even more complex? Absolutely. Even before reaching the rasterizer, there was still plenty of room for more features.

Mesh Shaders and Amplification Shaders

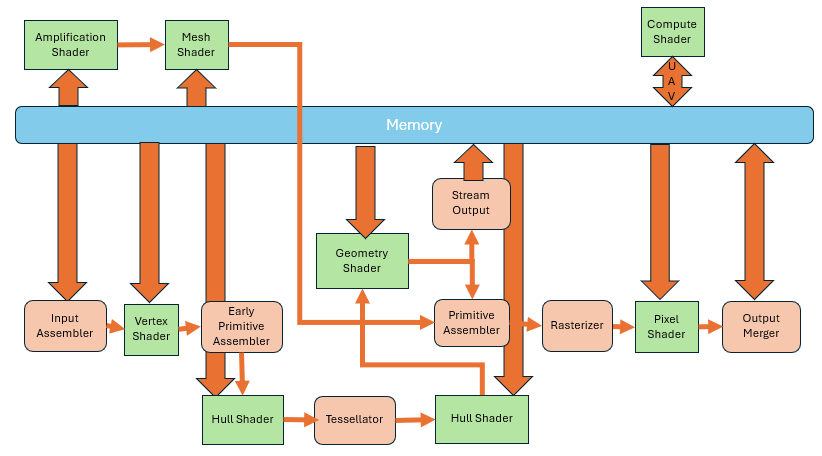

The parts before the rasterizer, vertex shader, hull shader, domain shader, geometry shader etc. The real purpose of them was to transform and tessellate existing geometry data and finally send it into the rasterizer. But all of these stages still rely on input geometry data. To render more complex objects, you have to feed in more complex data. To solve this, you need the GPU to generate a lot of detailed geometry even when starting from little or no input.

NOTE

While Compute Shaders can do this with arbitrary read/write, they can't connect to the rasterizer.

This gave rise to the Amplification Shader and Mesh Shader.

The Amplification Shader decides how many times to run the Mesh Shader. The Mesh Shader generates the actual geometry (primitives).

At this point, the input is no longer a primitive, but a small grid of geometry called a Meshlet. When a Meshlet is sent into the Amplification Shader, it can determine whether it needs further processing. If needed, it is passed to the Mesh Shader, which then produces geometry with rich detail. While these two shaders can replace the old geometry pipeline, support from GPUs and software is still relatively limited.

In current GPUs, they coexist with the traditional pipeline as optional components.

Ray Tracing Pipeline: A New Frontier

wip