- Published on

Teach My Girlfriend GPU 1: graphics pipeline basics

- Authors

- Name

- Yue Zhang

- Pixels and Color: The Smallest Unit of an Image

- How Images Get Displayed: Framebuffers and the GPU’s First Job

- When Processing Is Needed: Introducing Programmable Units

- Rasterization: Turning Triangles Into Pixels

- Depth Testing and Occlusion

- How Geometry Is Stored

- Transforming Objects in Space

- The GPU Rendering Pipeline

- CPU vs. GPU: Different Strengths, Perfect Partners

- Wrapping Up: What’s Next forthe GPU?

In this series, we’re not diving into code, APIs, or technical jargon right away. Instead, we’re taking a step back to look at the why behind GPUs — why they exist, how they evolved into what they are today, and what makes them tick.

GPUs — short for Graphics Processing Units — really started becoming a thing about 20 years ago. Back then, only graphics professionals cared about them. But now? Everyone’s talking about them. From video games and movies to AI and crypto mining, GPUs are everywhere. Any field that needs serious computing power probably relies on them.

This series will focus on the GPU itself — its structure, its functions, and how it evolved. We’re not going deep into computer graphics theory or image-processing tricks. And we’re definitely not assuming you know any APIs or programming. The goal is to unpack this amazing chip from the ground up. Let’s start with the basics: images.

Pixels and Color: The Smallest Unit of an Image

To a computer, an image is just a big grid of pixels. Each pixel holds color information, usually stored as three numbers — one each for red, green, and blue. These are called the RGB channels, and each one typically uses 8 bits (or 1 byte), which means a pixel usually takes up 4 bytes. As display tech improved, we started using more bits per channel — 10, 12, even 16 — which gives us more detail and a wider range of colors. But the core idea stays the same.

How Images Get Displayed: Framebuffers and the GPU’s First Job

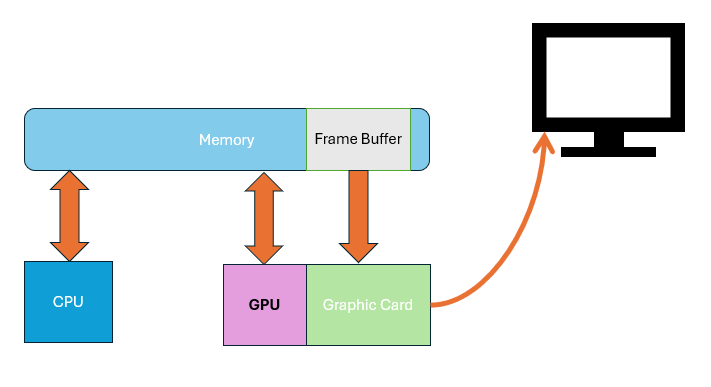

To display an image on screen, the computer first needs a chunk of memory called a framebuffer. This is a 2D array in memory, where each section corresponds to a single pixel. Most systems use 32-bit alignment — that’s RGB (24 bits) plus an extra 8 bits for alpha, which represents transparency.

Once the image is in the framebuffer, the graphics card's job is to pass that data to the monitor.

NOTE

At this point, Graphics card is just acting like a delivery truck — not doing any real processing yet.

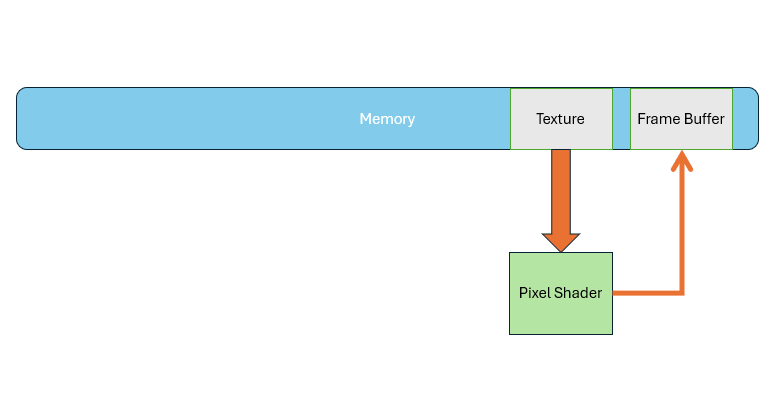

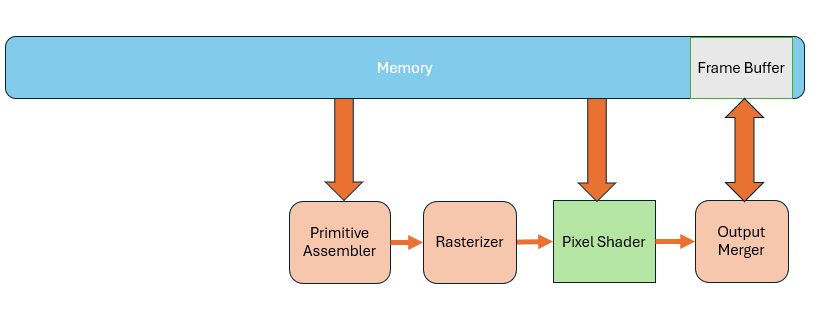

When Processing Is Needed: Introducing Programmable Units

NOTE

How the coordinate maps to the texture, how the data is fetched, and how the output is written back to memory — you don’t have to worry about that. All of that is handled by dedicated hardware.

Rasterization: Turning Triangles Into Pixels

Let’s go one step further.

What if our input isn’t just a static image, but an actual 3D object? These objects are usually made up of simple shapes — like points, lines, triangles, or quads. We call these basic shapes primitives. For simplicity, we’ll focus on triangles.

So how do you go from a pile of triangles to actual pixels on screen?

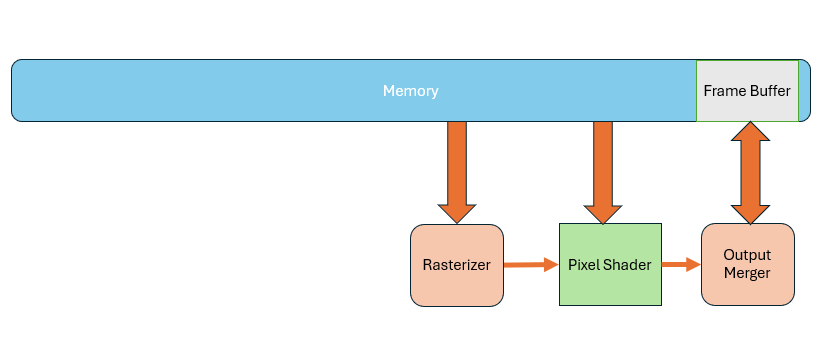

Before those triangles can reach the Pixel Shader, we need a stage that figures out which pixels are covered by each triangle. This process is called rasterization.

Rasterization is a fixed-function stage — meaning the algorithm is predefined and executed by dedicated hardware for performance. It's not programmable.

That’s why we refer to it as a fixed-function pipeline unit.

Depth Testing and Occlusion

Of course, when multiple triangles overlap the same pixel, the GPU has to decide which one is visible.

This is handled in a stage called the Output Merger, which performs depth testing using the Z-buffer. Based on depth values, it determines which fragment survives and makes it to the screen.

This, too, is handled by fixed-function hardware.

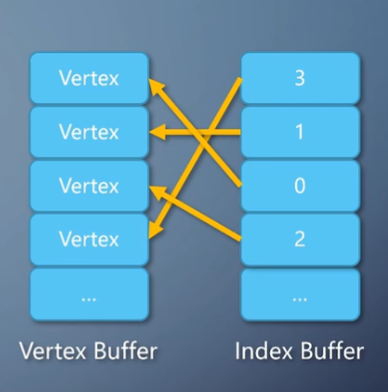

How Geometry Is Stored

Now let’s look at how 3D geometry is stored.

First, we have a set of points scattered in 3D space. These are called vertices.

Each vertex usually carries more than just position (x, y, z) — it might also include direction (normal), color, or texture coordinates.

The data for all these vertices is stored in a Vertex Buffer.

Next, we need to connect those vertices to form triangles. For that, we use an Index Buffer — it stores integers that represent which vertices form each triangle.

With the Vertex Buffer and Index Buffer together, we can define full 3D objects.

Before rasterization begins, the vertices need to be assembled into triangles, any parts outside the screen must be clipped, and edge equations for the triangle need to be computed — only then is the data sent into the rasterizer. The GPU contains a Primitive Assembly Unit that reads these buffers, assembles primitives, and sends them into the pipeline. This too is a fixed-function stage.

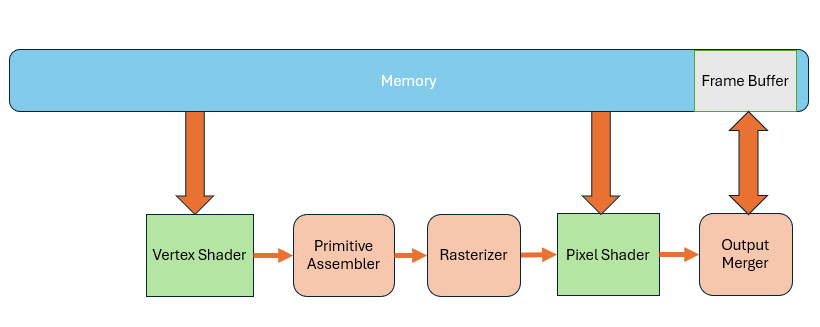

Transforming Objects in Space

Now let’s say we want to move the object around, view it from different angles, or adjust the camera. The object stays the same in geometry, but its appearance on screen needs to change. To achieve this, each vertex needs to go through three transformations, each represented by a 4x4 matrix:

- World Matrix – places the object in the global scene (position, rotation, scale)

- View Matrix – transforms the scene into the camera’s point of view

- Projection Matrix – projects 3D coordinates onto a 2D screen, simulating perspective

These transformations convert the vertex from object space → world space → camera space → screen space. Originally, GPUs had fixed hardware to perform these steps. For example, the GeForce 256 released in 2000 included a Transform & Lighting (T&L) engine to handle these transformations in hardware.

But for flexibility, this approach evolved quickly into a programmable model, using small programs called Vertex Shaders.

Each Vertex Shader processes a single vertex and applies all necessary transformations.

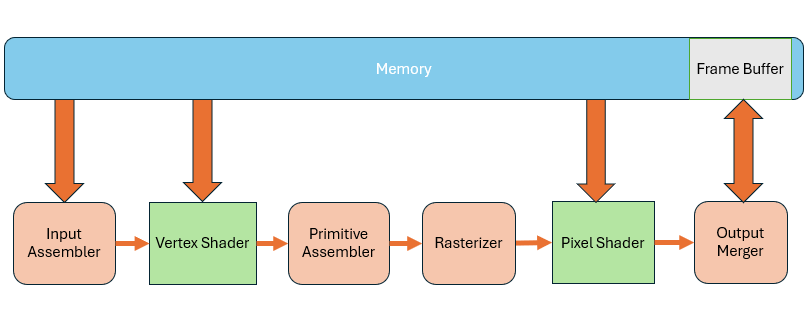

The data for each vertex can be stored in different formats, depending on the needs of the application. The Vertex Shader doesn’t need to know how this data is laid out in memory — it just processes values once they’re provided. That’s why we need a way to describe the format of each vertex ahead of time. This is handled by a fixed-function pipeline stage called the Input Assembler.

The Input Assembler reads raw data from the Vertex Buffer, interprets it according to the provided format description, and assembles complete vertices to be sent into the Vertex Shader.

The GPU Rendering Pipeline

This kind of graphics pipeline architecture became the mainstream design for GPUs in the 2000s. It effectively freed the CPU from having to handle large volumes of repetitive rendering operations. With GPUs handling these tasks efficiently and in parallel, the CPU could focus on logic and control. And it’s precisely this hardware-based graphics rendering capability that gives the GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) its name. To put it bluntly — if a chip can’t render graphics, calling it a GPU is just a scam.

To summarize: whether it’s a Vertex Shader or a Pixel Shader, each program is highly focused — it processes a single unit of data, returns the result, and doesn’t care about how the data is fetched from memory or where the output goes. That’s all handled by the rest of the pipeline.

CPU vs. GPU: Different Strengths, Perfect Partners

The CPU is great at managing small amounts of complex, branching logic. The GPU, meanwhile, excels at applying simple logic to massive amounts of data in parallel. They’re designed to complement each other — the CPU orchestrates, while the GPU executes en masse.

Wrapping Up: What’s Next forthe GPU?

Originally, the GPU was just a dumb image mover. But over time, it gained programmable features that made it central to modern graphics processing. Shaders are highly focused: they process one piece of data at a time, and the GPU takes care of everything else — like a callback function that gets automatically applied wherever it’s needed.

Because of this highly parallel, data-driven design, GPUs are now used in far more than just rendering. And the story doesn’t stop here.

In the next episode, we’ll explore how GPUs are evolving — expanding beyond graphics into areas like general-purpose compute, ray tracing, and AI.

Stay tuned!